5 Pillars of Teaching in 2025

Walk into any classroom today, and you’ll find something remarkable: not a group of kids who learn the same way, think the same way, or even behave the same way—but a spectrum of minds, each processing the world through a different lens. Sure, the Bell Curve still exists... but this is the reality of education in 2025: every class is neurodiverse.

And yet, many of the tools we give teachers are still built for the classroom of 1995... but with iPads.

We’ve handed educators a job that now involves navigating learning differences, mental health, executive functioning, tech-related attention issues, and academic standards that only get more intense each year. If that sounds like too much—it’s because it is.

But instead of adding more to teachers’ plates, can't we just change the plate?

To truly reach today’s students, especially in neurodiverse settings, teachers need a framework that helps them teach smarter—not harder. One that helps them connect with students at a deeper level, make learning accessible to every type of brain, and build classrooms where all kids can thrive.

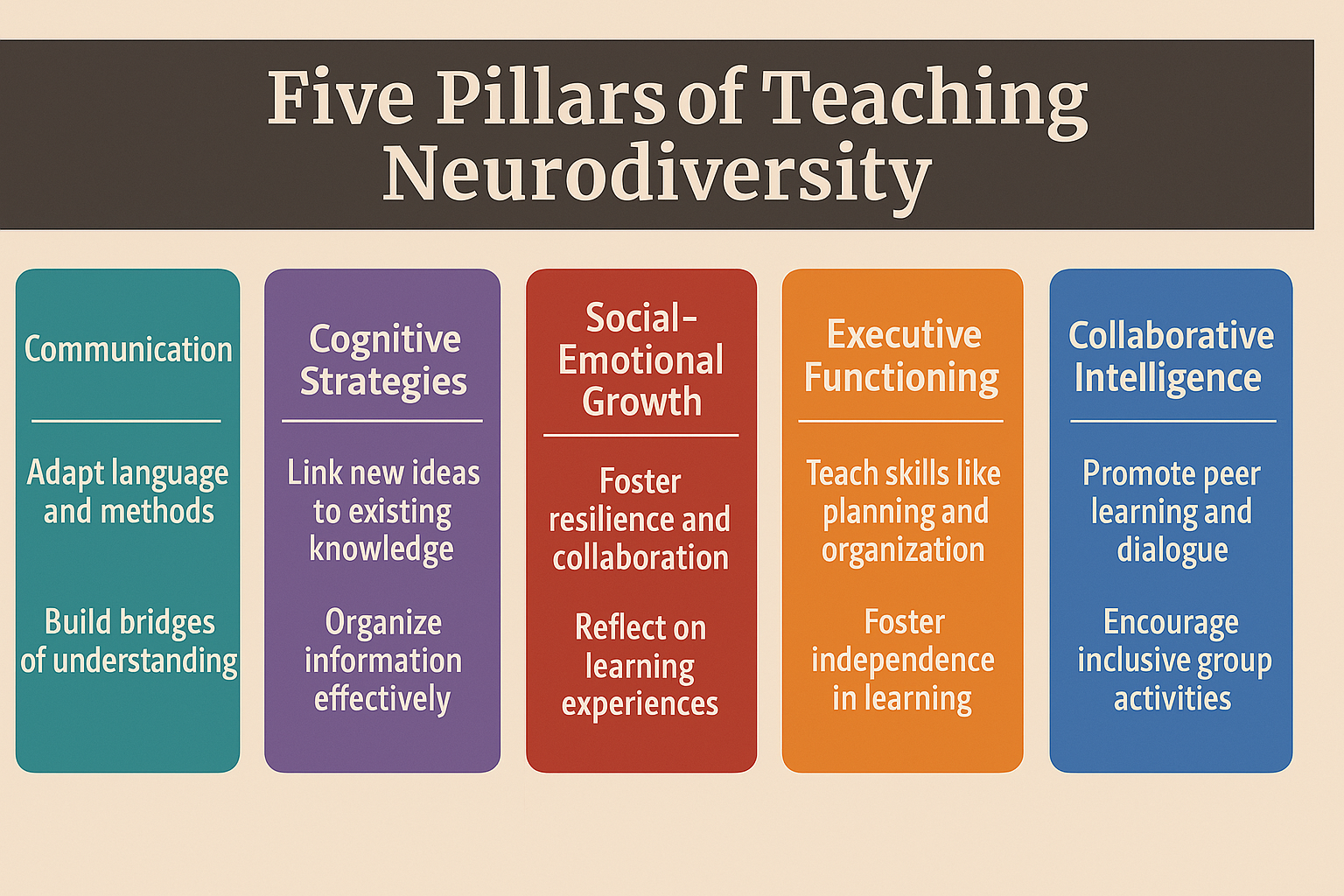

I would like to call this framework the Five Pillars of Teaching Neurodiversity.

1. Communication That Connects

Good communication is more than just clear instructions—it’s about meeting students where they are. That might mean using visual aids for students who think in pictures, scaffolding directions into manageable steps, or using metaphor and storytelling to deepen understanding.

In neurodiverse classrooms, teachers have to be communication designers. This includes tone, pacing, body language, and the way questions are framed. It means tuning in to how students receive and process information—and adapting accordingly. When a student says, “I don’t get it,” the neurodiverse-savvy teacher sees this not as resistance but as an invitation to communicate differently.

2. Cognitive Strategies That Build Transferable Thinking

Teaching content isn’t enough. If we want students to retain, apply, and connect what they learn, we have to teach them how to think about thinking.

That’s where cognitive strategies come in. Tools like schema activation, conceptual transfer, chunking, dual coding, and metacognitive modeling help students make sense of information in ways their brains can hold onto. In a classroom where neurodiversity is the norm—not the exception—these strategies aren’t extras. They’re essential.

Teaching kids how to think—not just what to think—prepares them to learn independently, apply knowledge across settings, and build their own mental frameworks for success.

3. Social-Emotional Strengthening

A neurodiverse classroom isn’t just academically complex—it’s socially complex too. Some students have highly tuned emotional sensitivity. Others may struggle to read social cues, regulate behavior, or cope with anxiety. This isn’t a problem—it’s a dynamic to be navigated.

Social-emotional strengthening isn’t about “fixing” behavior. It’s about teaching skills: empathy, collaboration, emotional regulation, and conflict resolution. That might look like guided peer discussions, reflective journaling, class meetings, or simply naming emotions in the moment.

When students feel emotionally safe and understood, they take more academic risks, engage more deeply, and connect more meaningfully—with content and with each other.

4. Executive Functioning Support

In every classroom, there are students who forget what’s due, can’t manage their time, or lose focus halfway through a task. These aren’t signs of laziness or disinterest—they’re signs of executive functioning differences.

Teachers who understand this shift their role from enforcer to coach. They model planning, break down tasks, and use tools like checklists, timers, and visual schedules. They build routines that reduce cognitive load and explicitly teach strategies for goal-setting, organization, and reflection.

These supports don’t lower expectations. They raise capacity. And over time, they help students develop the internal tools they need to succeed—inside and outside of school.

5. Collaborative Intelligence

In a neurodiverse world, intelligence isn’t just what happens inside one mind—it’s what emerges when minds work together. Collaborative intelligence is the ability to learn through shared ideas, diverse perspectives, and mutual effort.

In these classrooms, students don’t just work in groups—they learn how to work in groups. They build shared goals, navigate disagreement, and co-construct meaning. They contribute their strengths and rely on others’ strengths in return.

You’ll see classroom layouts that promote dialogue and shared exploration. You’ll hear group discussions that deepen understanding through respectful back-and-forth. You’ll witness students reflecting not only on what they learned but how they learned from each other.

This isn’t chaos. It’s intentional. It’s a culture built on interdependence and belonging—where students take shared responsibility for learning and contribute meaningfully to their classroom community.

Here are just a few things you might notice in a classroom practicing collaborative intelligence:

Students building knowledge together through discussion, questioning, and shared experiences.

Teachers facilitating, not directing, group problem-solving and inquiry.

Flexible workspaces that support movement, technology use, and peer-to-peer learning.

A classroom culture where students are empowered to help one another grow—academically, emotionally, and socially.

Collaborative intelligence isn’t soft—it’s strategic. It builds cognitive empathy, self-awareness, and communication skills students will use the rest of their lives.

Final Thoughts

If teaching feels harder than ever—it’s because it is.

But the solution isn’t longer hours, stricter discipline, or more content. It’s smarter systems rooted in how real kids learn. These five pillars—communication, cognition, social-emotional strength, executive function, and collaboration—don’t add more to the job. They are the job.

And when we get these right... we teach kids.